As many of my regular readers will recall, last year I developed very serious post-surgical chronic neck pain that extends from the base of my neck, across my right shoulder, down my right arm and clear through to the fingers of my right hand.

The pain in my right shoulder and arm feels like a sharp steak knife cutting into my flesh and varies between simply painful to being so intense at times that I have to go to bed in the middle of the day to try to get my mind off the pain.

Chronic post-surgical pain was for me a wholly unanticipated outcome, so we’ve given a lot of thought to possible explanations and to whether or not there might be some way of correcting the problem.

Initially, we thought that scar tissue on peripheral nerves nearby the surgery incision area might have formed and be pushing against several major nerves in the vicinity of where these major nerve bundles enter the spinal cord. Descriptions of compressed nerves sound to me quite similar to what I’ve been experiencing.

For many months I was needlessly further distressed because the neurosurgeons at Tongren Hospital here in Kunming insisted that what I was experiencing was not a normal consequence of their work, and they could not offer any possible explanation for what had obviously happened to me.

So at the end of last year, my Dad switched his neuroscience research focus from primarily regenerative medicine to pain management research and clinical options for me.

Over the last few weeks Dad has again been traveling to different countries in Europe and North America and has interviewed highly experienced neurosurgeons, with special thanks to the world-class neurosurgical team at Indiana University.

As it turns out, Dad has learned that acute post-surgical peripheral nerve pain is not as uncommon as we had originally thought.

Plainly there are always risks when opening up the spinal cord, and experienced neurosurgeons advise against any kind of cord surgery unless absolutely essential – this because operating on the spinal cord frequently results in “unintended consequences” … no kidding!

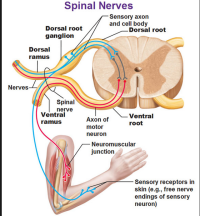

A common enough result of operating on the actual spinal cord, as opposed to just repairing vertebral bone damage, is that nerve tissue gets stretched at the intersection where major peripheral sensory nerves enter the central nervous system.

How’s This Work?

Certain readers may be interested in how major peripheral sensory nerve bundles enter and get spliced into the spinal cord … and how any type of spinal surgery can affect these spinal nerves on a permanent basis, sometimes leaving the patient in chronic pain for years.

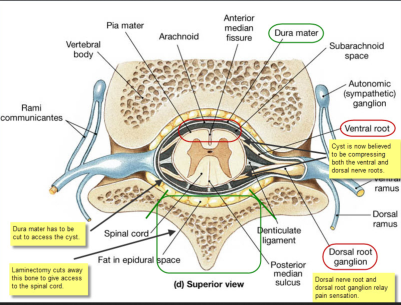

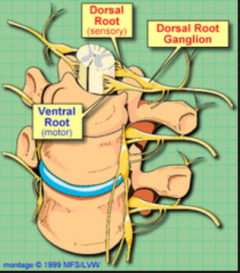

From the diagram below you can see there are two blue tube-like structures that enter the spinal cord on the left and right … these are called the dorsal root ganglia. The dorsal root ganglia feed mostly sensory nerve roots/fibers directly into the spinal cord.

On the diagram I have circled in green the area where I had my laminectomy, which means cutting away vertebral bone to access the spinal cord.

In my case, entering the cord was necessary to remove large fluid-filled cysts (circled in red) that were growing quickly and ascending into areas above my original C-6 injury to choke off nerve control of my breathing.

Performing a laminectomy and then cutting open the Dura Mater to gain direct access to the ventral (front) side of the spinal canal has clear potential to stretch the nerve fibers inside the spinal cord.

This is because the cord itself has to be pushed hard over to one side to enable access to a ventral cyst when the surgeon has entered the spinal column from behind.

The problem with this is that once a patient has been “sewn” back up, some of the spinal nerves remain stretched and do not return in their original positions.

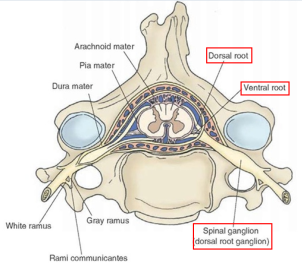

Another view of how the spinal nerves enter the spinal cord through the dorsal root ganglion

As some readers may be able to imagine, stretching major peripheral sensory nerve tracts where they splice the spinal cord risks serious consequences for the patient.

It is quite common that this stretching of sensory nerves can result severe post-surgical nerve pain, as has happened to me. Some patients report a reduction in the intensity of pain over the course of a year or two, but it’s not yet clear to me if the throbbing pain ever quite goes away. But that’s my hope … that over time the stretched nerves will reposition themselves.

As for pain levels, I would say my neck/shoulder pain varied between 8 and 9 every single day for the first eight months after surgery in May 2013, and today, a year later, pain levels have receded a little, back to a 7 or 8 depending on my sitting position.

For instance, it is much more comfortable for me to sit in my power wheelchair because I can recline the back rest as opposed to my manual chair that sits me in a constant upright position, causing pretty constant agony.

An illustration of the complex pathways of Spinal Nerves

A global picture of how the dorsal root ganglion fits into the spinal vertebrae

Once I learned from Dad’s recent investigations the likely reason for my chronic neck pain, somehow this helped me in dealing with the issue, because in my particular situation the operation that resulted in the neck pain was absolutely essential for survival.

Indeed, by the time of my surgery a year ago here in Kunming, I was already having serious trouble breathing, so surgery for me was life-critical.

I just wish the Kunming surgeons had been more forthcoming and alerted me to the potential side effect of severe post-surgical neck pain so I did not spend so many months after surgery thinking I was losing my mind.

In all these circumstances, I do accept the risks and “unintended consequences” that always come along with spinal surgery. Frankly, though, I find it extremely hard to accept that my surgeons told me point-blank and repeatedly that they had never ever before had any patient report the kind of pain I had complained about for so many months.

This may be due to the cultural differences in pain culture that

was discussed briefly in a prior blog post. Maybe so.

Post-Laminectomy Syndrome

However, a few months ago I met in Kunming a Sri Lankan patient who is paraplegic, and he, too, had come here for spinal cord surgery to remove multiple cysts in his spinal cord canal.

This fellow is today back home in Sri Lanka, but I’ve learned he has been repeatedly calling Tongren Hospital to complain about chronic thoracic pain that is so debilitating he can no longer work.

There is an actual name for this pain issue. It’s called “Post-Laminectomy Syndrome.”

The bottom line is that spinal surgery is sometimes essential for survival, but the risks need to be made known to the patient before surgery and critically evaluated.

It is reported that as many as 75% of spinal cord injury patients end up with some type of spinal cyst of varying size. This results from internal cord scar tissue impeding the free circulation of Cerebral Spinal Fluid (“CSF”).

However, I have concluded that unless the cyst is actually affecting motor function or critical organs, then I would think twice about having a cyst removed.

From bitter experience, I can tell you that having severe chronic neck pain and barely being able to sit up in a manual wheelchair is another challenge that could and should be avoided by spinal cord injury survivors who do not absolutely need to have this surgery.

Looking Ahead + Summing Up

In my next blog post, I will sum up the last dozen posts on the Kunming spinal cord injury program – this for the particular benefit of fellow spinal cord injury survivors who may be thinking about travelling to Kunming, either for surgery or to participate in the Kunming Walking Program.